25 Jan Urafors History by Birgitta Strand

Urafors History, by Birgitta Strand

The following essay is history of Urafors axe factory, written by Birgitta Strand. The Swedish pdf document was transcribed from pdf “image” format to digital by Rasmus Pettersson Vik. I used Google translate to convert to English. PLEASE – feel free to help me correct errors in the translation. Some questionable words are marked in red.

The original pdf (image version) can be seen HERE.

The pdf (digital transcribed version in Swedish by Rasmus) can be seen HERE.

(Check out Rasmus Pettersson Vik’s blog website and his online folder which has loads of great axe-related historical documents, videos and photographs.)

-Diana

Title Page

Page 1

University of Gävle-Sandviken – Individual courses and local lines

Ullungsfors manufacturing works and its development to Urafors ax factory until 1918

Supervisor: Ragnar Bjers

by Birgitta Strand

1980-08-22

(Transcribed from the original by Rasmus Pettersson Vik, 2020-11-24)

Page 2

Table of Contents

Introduction ………………………………………….. 2

– Purpose and delimitation ………………………………………….. 2

The foundation ………………………………………….. 3

– Production at the start ………………………………………….. 3

– New owner ………………………………………….. 3

– New product ………………………………………….. 4

– Raw materials ………………………………………….. 4

Two more owners ………………………………………….. 5

– The work in the smithy ………………………………………….. 5

– Work performed by children ………………………………………….. 5

– Working hours ………………………………………….. 5

– Coal ………………………………………….. 5

Production of axes and bark iron ………………………………………….. 6

– Stagnant business ………………………………………….. 6

Urafors ax factory moves to Edsbyn ………………………………………….. 7

– Sale of the old smithy ………………………………………….. 7

– The new smithy is being built ………………………………………….. 7

The smithy becomes a factory ………………………………………….. 8

– Working conditions, wages and working hours ………………………………………….. 8

– The production ………………………………………….. 8

Factory machines and equipment ………………………………………….. 9

Closing ………………………………………….. 10

Notes ………………………………………….. 11

Sources ………………………………………….. 12

Appendices

Page 3

Introduction

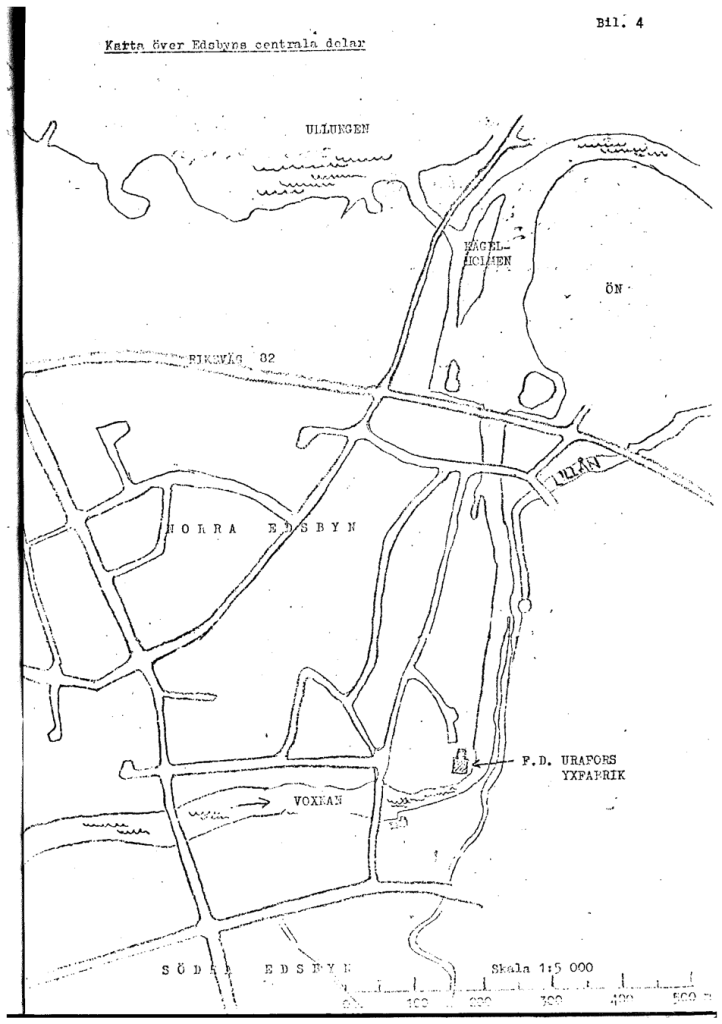

The village Ullungsfors in Ovanåker parish is named after its location by the lake Ullungen’s tributary. The village was dominated during the end of the 19th century by agricultural population. There was a customs mill, a customs saw and the smithy, the development of which is the subject of my essay. Today, there is a small sawmill industry in the village and a carpentry industry. The residential development has increased sharply and the village’s population now largely has its livelihood in Edsbyn. The building, which once where Ullungsfors Manufakturverk is today sandwiched between newer buildings. My essay is largely based on taped interviews with three grandsons to one the founder of the manufactory. Two of these have worked all their lives as blacksmiths, one of whom is his own operating time at Urafors ax factory in Edsbyn. The third interviewee is a homeowner. Additional materials that I have used are notes kept by CO Åberg, ULMA’s archive, the newspaper Ljusnan, photos, purchase contracts, minutes and diaries.

Purpose and delimitation

The purpose of the essay is to follow the smithy’s development from village smithy to ax factory. The essay wants treat the development at Ullungsfors Manufakturverk until 1900 and thereafter continuation, in Edsbyn as Urafors Yxfabrik until 1918. Production continued in Ullungsfors after is 1900. Even in Edsbyn production continued after 1918 but these periods are not treated in the essay.

Page 4

The foundation

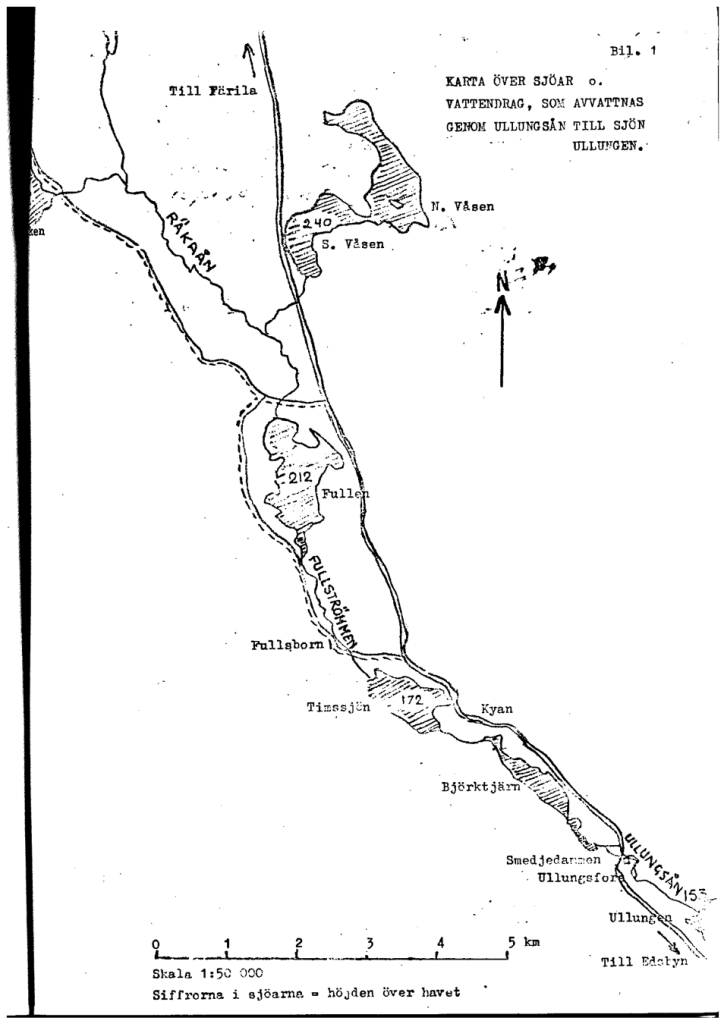

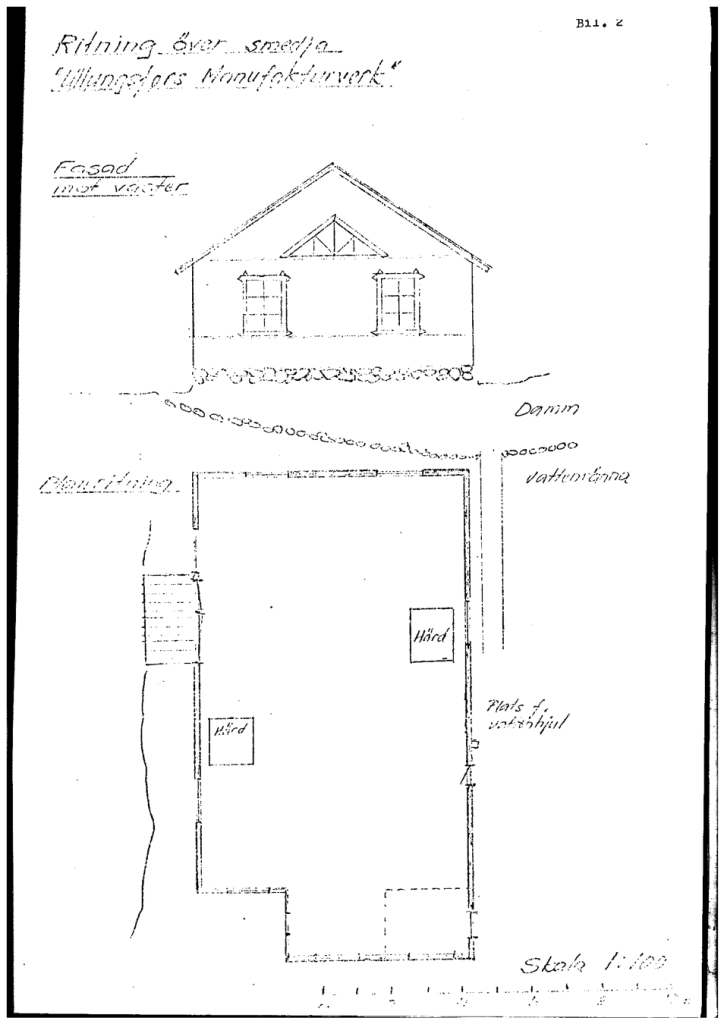

“Hälsingland, especially the northern part, has long been known for its skilled blacksmiths.” This says P. Norberg in a special print for the friends of mountain management in 1954. Admittedly, Ullungsfors is in western part of Hälsingland but expressions can apply generally to the entire landscape. Ullungsfors manufactory in the village Ullungsfors, about 3km northeast of Edsbyn community was founded on 1840s by two villagers. These were the sergeant in Hälsingland’s regiment Jonas Jonsson Forsell b. 1809, died 1893, married to Lisbeth Pehrsdotter b. 1808, died 1889, and the soldier no. 103 in Hälsinglands regiment Olof Olsson-Uhr, born 1804, died 1901, he was married to Anna Olofsdotter born 1809, died 1887. The Jonsson-Forsell family had two children and the latter family nine children (Swedish genealogical register, Ovanåkers parish X 36).The smithy is located by Ullungsån, which has its origins by Lake Värasen with a height above sea level of 393m. The river finally flows into Voxna älv, where it has an elevation of 153 meters above mean sea level [1]. The forge, which there are still remains of, is on land separated from Stålbo no. 1 and Norra Edsbyn 11: 1. Current property designation is Norra Edsbyn 11:17. From the beginning, according to notes, the smithy had a wall and two forging hearths. The wheelhouse, which was placed on the side contained a larger and a smaller water wheel. The big wheel was meant for the hammers and had a rough wheelbarrow, which extended into the floor of the smithy. At an angle to this wheelbarrow where the hammers were placed. The larger hammer “bundle hammer” was used to reach out the iron pieces with, since rolled iron did not occur. The smaller nail hammer went faster and was used for nail forging. The shaft of the hammers and also the cleaning rod were made of wood and must therefore be wedged with wooden wedges, a fair and often recurring work. The little water wheel finally had the task to pull the blower, which pumped air to the hearth [2].

Production at the start

In the smithy, most nails were made from the beginning and the smithy was therefore called the nail mill. The nails were used extensively for the shavings or pitched roofs, which were then the most common roof cladding. [3] They also forged plows, horseshoes, horseshoe stitching and worked with shoeing for sleds, sledges, trolleys etc. In addition, repairs were carried out that were becoming of a village forge.

New owner

Notes show that the two owners sold the manufactory to Olof Olsson-Uhr’s eldest son,Olof Olsson-Åberg in 1857 (born 1831, died 1900). In 1856 he had married Helena Forsell (born 1834, died 1874), daughter of the other owner Jonas Jonsson-Forsell. This marriage must undeniably have simplified the purchase and takeover of the manufactory. Olof Olsson-Åberg was then 26 years old old. On September 8, 1858, the young blacksmith applied for permission from the “Mining Office” to get his own factory stamp and to be allowed to erect “a bundle and two nail hammers”. The factory stamp would be UF, which stood for Ullungsfors or Urafors, which came from the father’s name Uhr. Permit was granted by the King in Council and the kingdom’s Commerce Collegium 12 January 1859 [4].

Page 5

New product

The forest in Ovanåker parish as well as Norrland in general had not had any major value until mid-19th century, excluding extraction of building timber and firewood. Around 1860, forestry companies began to be formed. These bought up forest, felling rights and the entire forest home, then came deforestation started largely thanks to Värmlanders, who were skilled forest workers. [5] At the same time, the machine-cut nail began to come and the hand-forged nail was outproduced. Demand decreased for the product that was most important to Ullungsfors Manufacturing works. Olof Åberg then saw the possibility of switching to the production of ax and bark iron forging, as forestry increasingly needed good tools. The manufacture of axes was a small part of the production in the beginning, but continued to grow and became the most important product for the company. [6]

Raw materials

The steel for the axes was of two kinds. In the edge and neck so-called iron with a high carbon content and in the rest of the ax softer steel, which was easy to forge. The carbon content of the steel can vary from about 0.03% to about 2%. The most the grades used have between 0.005 and 0.5% carbon. The higher the carbon content, the harder the steel became. [7] The egg steel came from Vikmanshyttan in Södra Dalarna, so-called CRU steel. The axe iron was produced with the Swedish Lancashire method, which was delivered from some ironworks in the area in the form of bar iron. How to transport the raw material to Ullungsfors went to, my sagesman was not entirely sure, but since the railway came to Edsbyn only in 1899, it can be assumed that the iron was transported by horse forks during the winter [8].

Page 6

Again two owners

Ax production increased and around 1870, exact year could not be obtained, Olof Åberg sold half the smithy of his brother Pehr Stålberg (born 1839, died 1920), who lived on the ancestral home N. Edsbyn no. 11. Olof and Pehr were sons of the soldier Olof Olsson-Uhr but took the names Åberg respectively Stålberg. In his early youth, Pehr Stålberg studied blacksmithing with a pistol and riflesmith Jonas Stålberg in Östanå, about 7 km east of Edsbyn (born 1817, died 1864). Jonas Stålberg was married to Lisbeth Olsdotter, sister of Olof Olsson-Uhr, one of the two founders. After completing his apprenticeship, Pehr took over Stålberg his teacher’s last name. [9] I have not been able to clarify the name Åberg’s origin. The two brothers did not work as partners in the sense that they had production and sales jointly, but they divided the forge into two departments. Åberg stamped his axes UF and Stålberg’s with PS. The [power]hammers and the blower were their common property. The number hearths were expanded from two to four and thus an equal number of blacksmiths could be prepared. [10]

The work in the smithy

During the period up to 1900, six adult men worked in the smithy. [11] In addition, several boys, most family members engaged in the work, more about that below. The smithy was often cold and draughty, especially in the mornings but with the heat from the hearths, the temperature rose and the heat was sometimes troublesome.To protect themselves from sparks and heat, the blacksmiths wore a leather chest cloth. It went from the throat down to the floor, says the sage. [12] The blacksmiths sometimes wore clogs according to pictures from this time. No further information on workwear has been available.In winter, the work began with crawling down into the wheelhouse in the light of the stick flare, to cut loose ice from the wheels. The balance on the wheels was disturbed, if the ice remained. This was a difficult and tiring one work for those who did this. [13]

Work performed by children

During the heyday of the nail forge, the children participated in the work by e.g. count nails. My sagesman tells that they had boards with holes, a dozen or a score, he was not sure of the number. For each full board a line was made and in this way one could keep track of the number of nails. [14] Later, the tasks increased for the young boys. Dammball boys worked to regulate the supply of water to the water wheels, by opening and closing a hatch in the pond. Depends on the blacksmith’s work rate at the hammer, a dustball boy could run several hundred times. The was to save on the water in the pond. Sometimes the water inflow was so low that the operation had to be stopped. During the dark season, the children had to light the blacksmiths with flares of tar sticks. The kerosene was considered too expensive and in addition did not keep the chimneys in the uneven temperature. During the 19th century, however kerosene lamps common, which was considered a major advance. [15]

Working hours

The work usually started at six in the morning and lasted for twelve hours but according to the sage took you take real breaks during the day for food and conversation.

Charring

In addition to the extensive work in the smithy, the blacksmiths must to some extent participate in the work the charring. The smithy’s annual need for charcoal was obtained by purchasing coal wood or leasing it piston shifts in a number of years. Chopping and charring are performed by coal miners, which according to my sagesman had a piecework price for work performed. The charring took place in lying miles, usually in the vicinity of the smithy. Horses for forging and driving of firewood etc. owned by the blacksmiths themselves. [16]

Page 7

Production of axes and bark iron

The ax and bark forging in Ullungsfors reached its peak in 1880 – 90. The production was completely craftsmanship and the annual production amounted to six to eight hundred dozen axes per year. The axes were sold over that fairly large area: parts of Norrland, Värmland and Dalarna. In Dalarna the axes were called”Kiayxor” or “Kyayxor”, as the smithy was located near the village of Kyan. The greetings, on the other hand, called the axes Uhrayxor, because it was the smithy of the Uhra boys. [17] The axes sold were actually half-finished. They lacked stems and were completely unpolished. A common job was re-stating old axes. The edge of the ax was cut off and new edge steel was poured in. People could come with a horse from i.a. The valleys to get axes rearranged. They had then collected axes for a long time and to get all the converted axes back, you sometimes had to leave someone ora few nights. [18]

Stagnant business

The two owners had three sons each, who worked more or less regularly in the smithy.

Pehr Stålberg’s sons were:

- Olof Vilhelm – born 1868

- Carl Erik – born 1870

- Jonas – born 1877

Olof Åberg’s sons were:

- Per Johan – born 1863

- Jonas Vilhelm – born 1868 (Emigrated to the United States 1891)

- Carl Olof – born 1873, died 1962

The latter was the one who later continued operations in Edsbyn. Notes by CO Åberg tells that at the age of 16 some of these youngsters had made their first axes and got them approved by their fathers. CO Åberg and Vilhelm Stålberg participated in the Gävle exhibition 1901 with their own axes and received there “Diploma for honorable mention for good axes”.

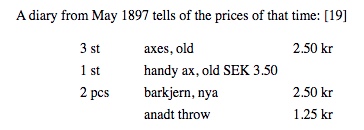

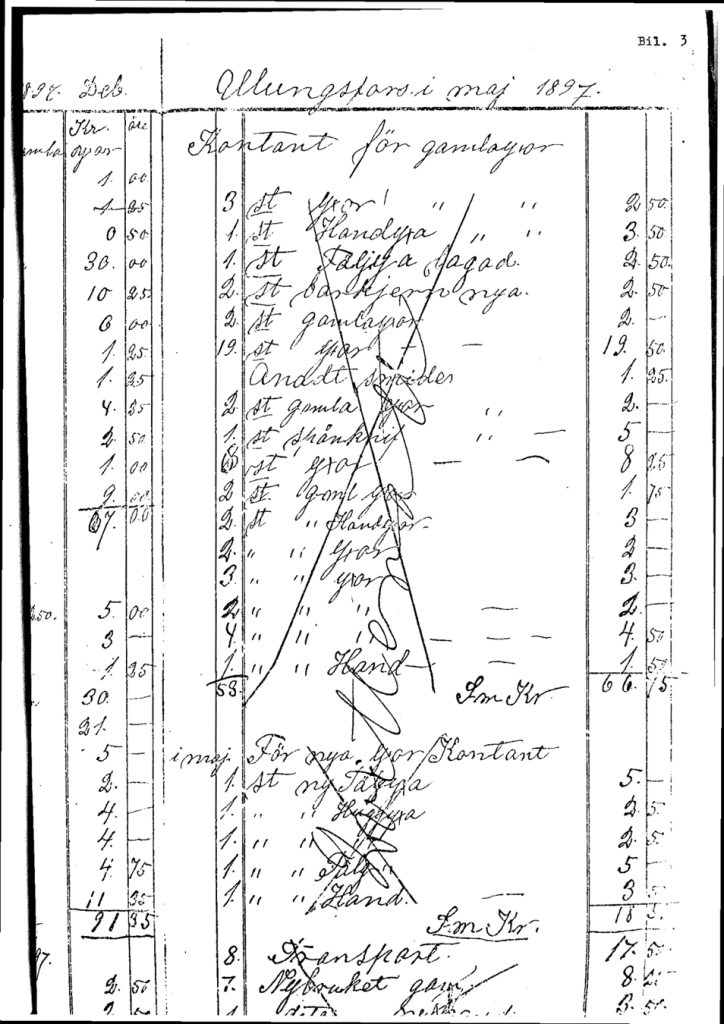

A diary from May 1897 tells of the prices of that time: [19]

From an “information about Ullungsfors Manufakturverk in Ofvanåker parish of Gefleborg county in 1900”, was the value during the year for sold axes and bark shovels SEK 9,929. Repairs of ditto SEK 1,834. Total 11 763 kr. The plant then had, as at the beginning, two water wheels of about 8 horsepower, which was most like could be taken out of the waterfall. The number of employees over the age of 18 was 6 (men). Appropriation taxed income 3,100 kr. The document is dated 28 February 1901 and signed by O. Åberg and P. Stålberg. Since Olof Åberg died on 18 August 1900, there must have been a mistake in the dating. [20] In the diary for the year 1900, CO Åberg has noted: Aug 18 an Paid kiss to dad 18.50 kr”22” Digging of graph 5.00 kr”22 for coffee at the funeral 15.00 kr”30 a bottle of juice v. The estate register SEK 1.25.

Page 8

Urafors ax factory moves to Edsbyn

n November 25, 1899, Olof Åberg’s youngest son Carl-Olof wrote a deed of purchase regarding land and water rights at Voxna älv in Edsbyn. The possibility of increasing operations in Ullungsfors was non-existent, as was not the case sufficiently watery. CO Åberg had in 1898 married Marta Persdotter, born 1875, from Knåda in Ovanåker parish and settled in Ullungsfors. There their first child Peter was born in 1899, later a blacksmith and one of my sages.The purchase included a quarry at Voxna älv, “Nils Jons skeckten”, owned by the widow Brita Olsdotter, Norra Edsbyn, located in the southeast corner of the purchased and merged land 4 öre 12 money land of the Kronoskattehemmanet Edsbyn no. 6 and 12 money lands of the Kronoskattehemmanet Edsbyn no. 15 in the probate documents merged under the name Norra Edsbyn no. 3. The purchase price for the land was SEK 1,100. SEK 900 was paid for the shafts. [21]

Sale of the old smithy

At Olof Åberg’s death, the Åberg branch sold its share in Ullungsfors Manufakturverk to P. Stålberg, who continued operations in Ullungsfors. The smithy was in use until the end of the 1950s. The building is there still left but in miserable condition.

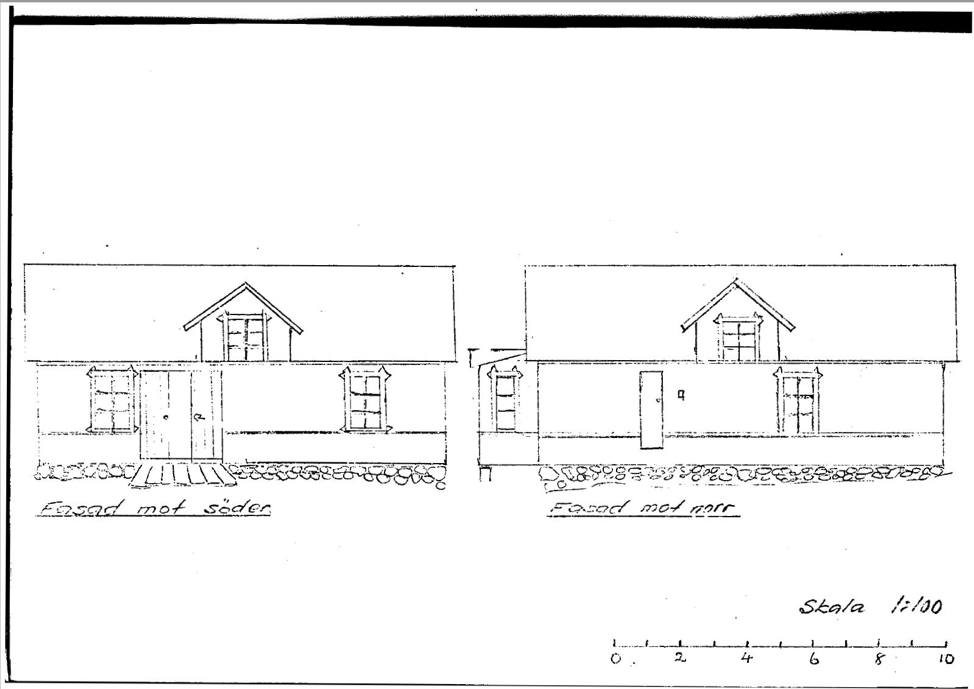

The new smithy is being built

CO Åberg moved to Edsbyn with his family in 1900 and began building the new smithy the same year at Edsbyströmmen after Voxna älv. The water wheels were now replaced with two turbines of about 36 horsepower. The factory had four hearths or coke ovens and soon received press, emery and grinding mills. [22] Dein the first years there was a lack of electric lighting but around the year 1904 the factory got electric power from its own generator, however, only for lighting in the factory and the dwelling house.

Page 9

The smithy becomes a factory

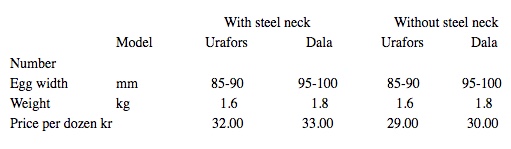

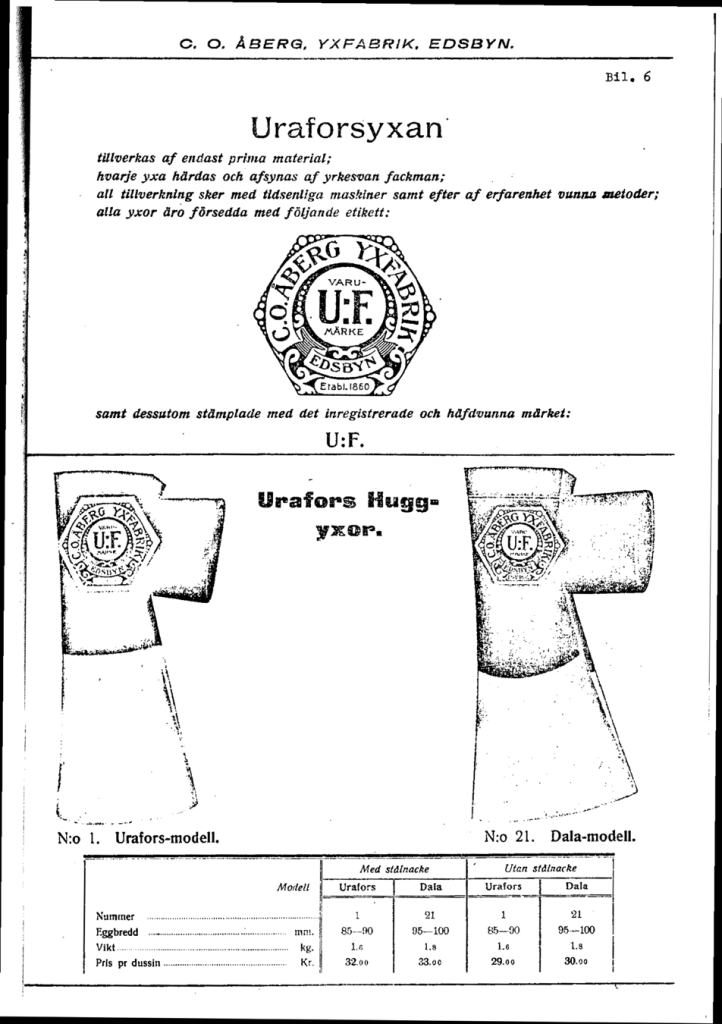

In the old smithy, the entire production of the ax was handled. Now the production was divided into different moments, where different people were responsible for e.g. pressing, polishing, steeling, grinding etc. Axes and bark spades were the big items. In 1910, CO Åberg published a catalog of the factory’s production and called this “anniversary catalog”, as 50 years had passed since the company was established in Ullungsfors. [23] The catalog contained a dozen different models of factory production but I have failed in my attempts to find it. However, I have found the 1913 catalog, which is called “Price list for Urafors Yxor”, where the following is taken from:

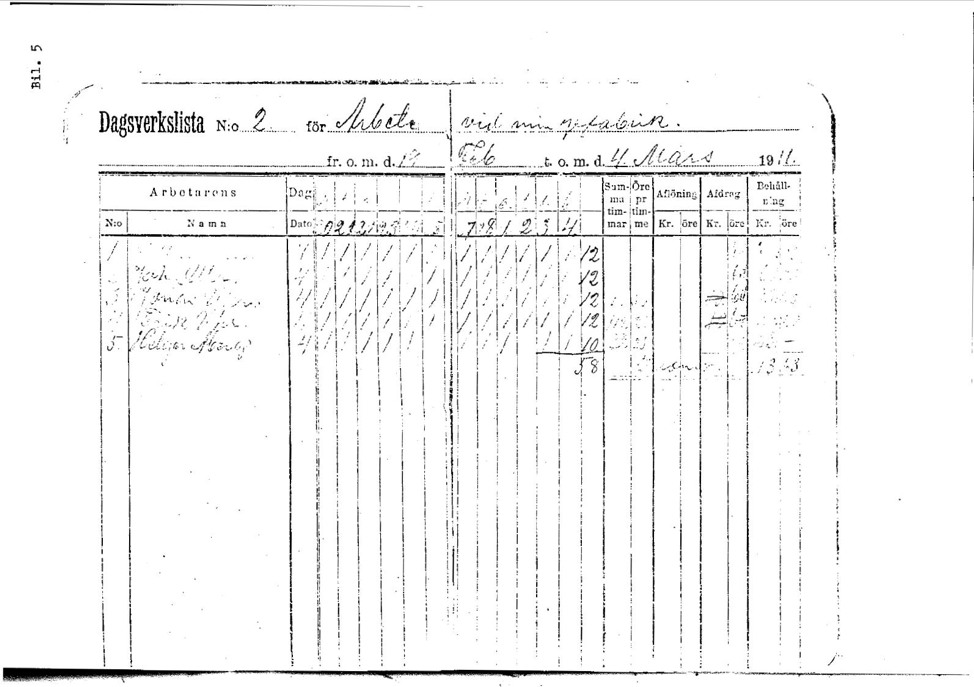

Working conditions, wages and working hours

In a “diary book for C. O Åberg, Edsbyn 1911” there is information that the factory then had 5 employees.They worked about 10 hours a day six days a week. The payment varied from about 25 – 67 öre per hour, depending on occupation, age and knowledge. The salary was paid every fortnight and could be used employee amount to SEK 27.50. The number of full working days was then 11, as Saturday was counted as half working day. The diary book has no information about the nature of work. The factory’s total wage cost for the five employees during the fourteen-day period 1911 were SEK 213.63. By 1912, the workforce had doubled and for an equally long period, the costs were then SEK 380.28.CO Åberg’s son Petrus, my sagesman, started working full time at the age of 13. He got to work as sledgehammer, handyman or pull in where he was needed.It was not easy to find skilled people in the area and therefore some employees came from other places the country. For example. a blacksmith and a grinder from Säter, a baler from Hultsbruk and another blacksmith came from Törnshammar. [24]

The production

Production increased thanks to increasingly mechanical production. In 1913, about 25,000 axes were made. [25] Regarding bark spades, I have no information. Uraforsyxan became a fairly large article in Sweden and gradually became known even outside the country’s borders. Norway and Denmark bought Uraforsyxor and Russia also belonged to the buyers, albeit to a small extent. Uraforsyxor was used in the construction of the railway line Egypt – Good Hope Cape. The factory manufactured 39 different models of axes, bark shovels and hoe picks. [26]

Page 10

Factory machines and equipment

The minutes kept during inspection and valuation of the manufacturer CO Åbergs in Edsbyn property with industrial facilities built there in Edsbyn, Ovanåker parish on 9 June 1916 ”. This is the title of a protocol where you can read the following about Urafors ax factory: “The factory building houses an ax smithy, grinding mill, emery workshop and packing room with an ax press with accessories and axles belonging to the machinery, pulleys and bearings as well as drive belts. The factory building includes an attached belt house to protect the belt line from the turbine house and water sump built together. The turbine housing belongs to turbine drum. With the current drop height, the turbine develops 35 horsepower, and more the same hears shoulders and bearings. In addition, there is a smaller turbine in the turbine housing which provides driving power to an electric generator similarly arranged therein for lighting for the factory and the house, etc.” The assessed value in 1914 was SEK 12,000.

Page 11

Termination

In 1918, the company was transformed into a simple company and the company name became CO Åberg och Co. Thus began a new era in the history of the factory. Production continued until around 1960, when the company was closed down. Documents show that CO Åberg called himself a blacksmith at least until 1906. In 1912 you can read from the minutes that he transferred to the title of manufacturer. CO Åberg died on March 27, 1962.

Page 12

Notes

[1] O. Johansson, “Ovanåker,” p. 26.

[2] CO Åberg, “Notes”.

[3] P. Norberg, “Vattensläggor …,” p. 232.

[4] “Resolution from the King. Majt ”.

[5] H. Lidman, “Ovanåkers socken,” p. 7.

[6] CO Åberg, “Notes”.

[7] Focus.

[8] P. Åberg, “sagesman”.

[9] Å. Stålberg, “sagesman”.

[10] CO Åberg, “Notes”.

[11] “Information from the Chamber of Commerce’s archives in 1900”.

[12] Å. Stålberg, “sagesman”.

[13] CO Åberg, “Notes”.

[14] P. Åberg, “sagesman”.

[15] CO Åberg, “Notes”.

[16] Å. Stålberg, “sagesman”.

[17] “ULMA’s Archive, No. 17761”.

[18] P. Åberg, “sagesman”.

[19] CO Åberg, “Diary from Ullungsfors”.

[20] “Information from the Chamber of Commerce’s archives in 1900”.

[21] Purchase deed, “No 1 and No 2”.

[22] “Tidningen Ljusnan, 29 June 1914”.

[23] CO Åberg, “Notes”.

[24] P. Åberg, “sagesman”.

[25] “Tidningen Ljusnan, 29 June 1914”.

[26] “Tidningen Ljusnan, 29 June 1914”.

Page 13

Sources

Unprinted sources

– Notes kept by the blacksmith CO Åberg

– Diary 1897 – 1900 from Ullungsforssmedjan, kept by CO Åberg

– Diary book 1911 – 1913 from Edsbysmedjan, kept by CO Åberg

– Interviews, taped with the following sages:

- Stålberg, W. born 1899

- Stålberg, Å. Born 1911

- Åberg, P.born 1899

– Commercial College Archives, Statistics Department Hld 1:75, year 1900,information about Ullungsfors Manufakturverk

– Purchase deed No 1, regarding “Nils Jons” horror

– Purchase deed No 2, regarding land purchase

– Resolution from “Kongl. Majt and the Kingdom’s Commerce-Collegium

– ”Records in the Dialect and Antiquities Archive, Uppsala (ULMA)

Press sources

Johannson, O. : Ovanåker, the fate of a Norrland parish through the centuries, Bollnäs 1937.

Focus reference book : second rev. uppl.

Lidman, H. : Ovanåker parish. A short parish description. Compiled in 1962.

Norberg, P. : Water sledges and small manufacturing workshops in Hälsingland. Reprint out “Magazine for the friends of mountain management”, Uppsala 1955.

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21